Designing a modern web-based application — Dropular.net

![]() One and a half years ago me and

Andreas

released a new version of dropular.net — a new kind of web app that runs completely in the browser. Today, this approach to designing web-based applications running client-side has become popular, so I thought I’d share some of the issues, approaches and design choices made during the development of Dropular.

One and a half years ago me and

Andreas

released a new version of dropular.net — a new kind of web app that runs completely in the browser. Today, this approach to designing web-based applications running client-side has become popular, so I thought I’d share some of the issues, approaches and design choices made during the development of Dropular.

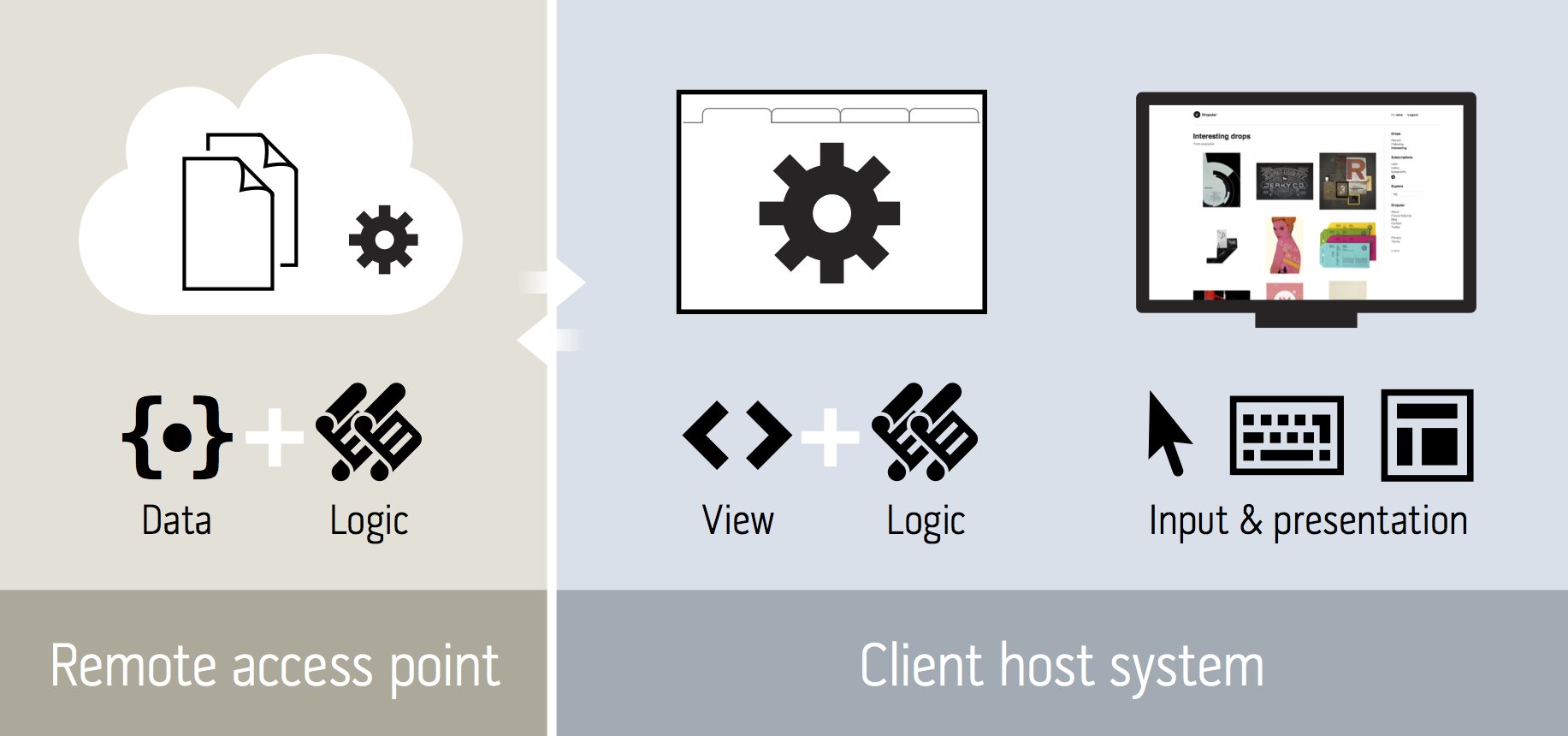

I designed Dropular just as I would design a desktop application — the UI and related logic runs on the host computer (client). The host knows how to present a GUI and the host knows about user input, end-user’s environment state and so on, making UI code running on the client-side the natural choice. Then again, there’s always data. Dropular.net communicates with one or more backend access points to read and write data, verify authentication and so on.

Basically, we serve only data from the access point and run almost all code in the client web browser:

When a client visits dropular.net, three files are sent as the response: index.html, index.css and index.js — view, layout and logic, respectively.

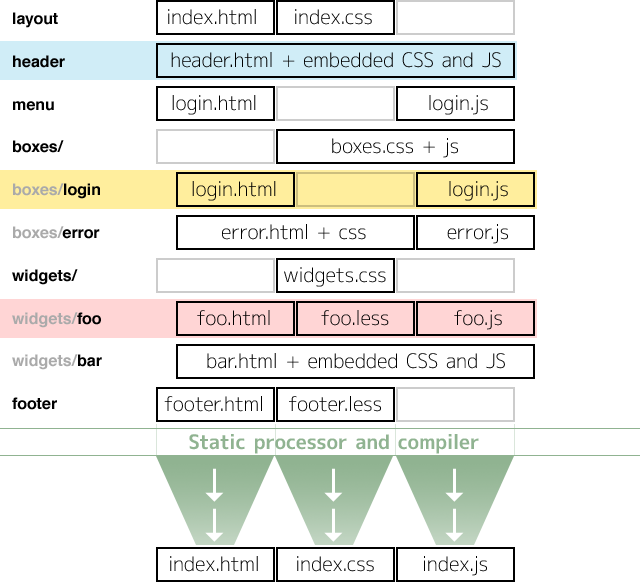

If you view the source of any of these files you might notice that the code looks suspiciously computer generated. That’s because it is computer generated. As part of Dropular, I wrote a web-app client-server kit dubbed oui which given a source tree compiles and produces a runnable index.html file (together with an index.js and index.css file).

Oui provides a CommonJS module interface and groups together LESS/CSS, JS and HTML into logical modules which are name-spaced:

Demo and source code

First, let’s have a look at the actual product and experience (since it’s invite-only). This is a screen cast of me using the current, live website:

Now, here’s a redacted snapshot of the Dropular source code: https://github.com/rsms/dropular-2010. Note that this code depends on oui and a few other open source projects.

Authentication

![]() In a model where the logic lives in the client, security is a different nut to crack. You need to deal with automatic re-authentication, network reconnection, server fade-over, etc.

In a model where the logic lives in the client, security is a different nut to crack. You need to deal with automatic re-authentication, network reconnection, server fade-over, etc.

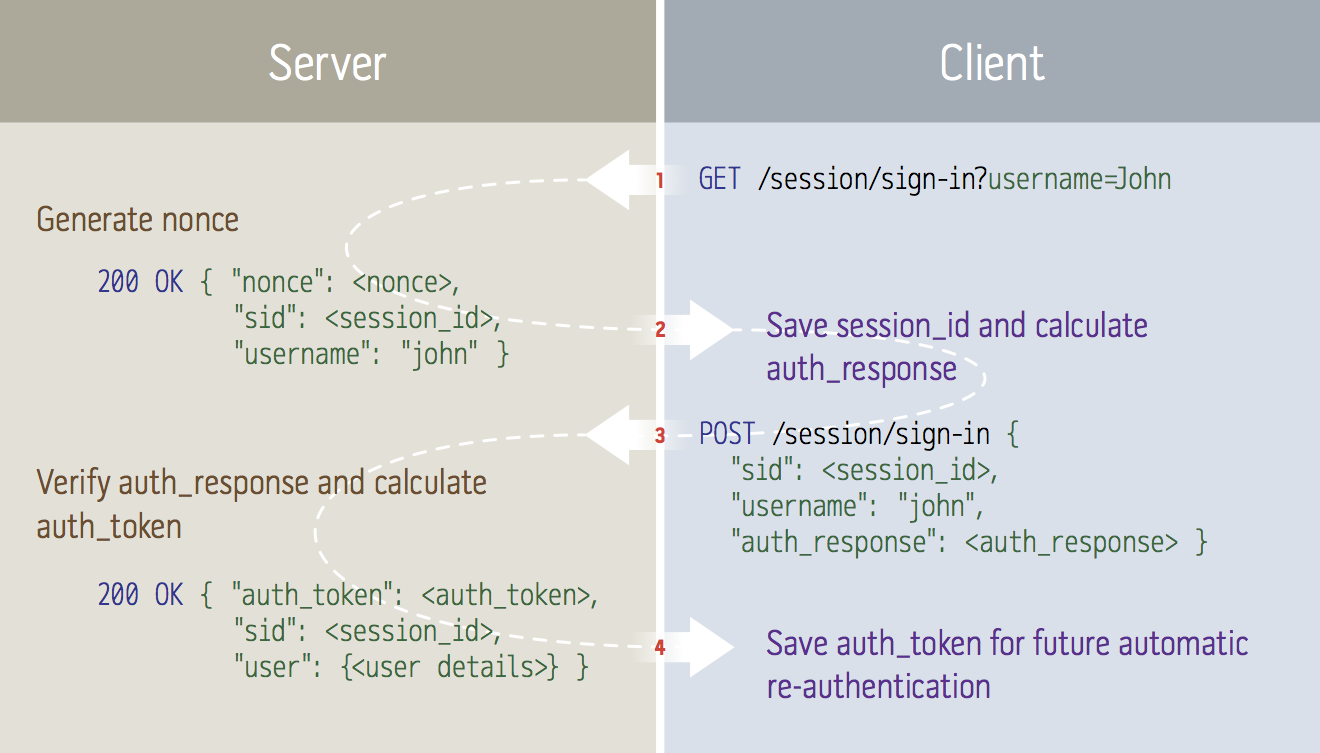

Authentication is performed in a two-step process, allowing an intermediate representation to be cached in the client, enabling automatic fail-over to other access points and automatic login when later visiting the site.

It goes a little something like this:

[Step 1] Client sends a request for challenge:

← GET /session/sign-in?username=John

[Step 2] The server:

- Verifies and fetches information about the user related to

username - Generates a UUID that is uses as a session ID

- Creates a temporary session object in memory, associated with that session ID

- Generates a

nonceusing:BASE16( SHA1_HMAC( server_secret, timestamp ":" random_data ) ) - Puts the

noncein the user’s session and registers a hook to clear the NONCE upon next request containing the associated session ID. - Responds to the client with the nonce and the user’s canonical username:

→ 200 OK {"nonce":<nonce>, "sid":<session_id>, "username":"john"}

[Step 3] The client:

- Stores the

session_idlocally, to be used for future requests - Displays a user interface where the user inputs her username and password

- Calculates the

passhash:BASE16( SHA1( username ":" password ) ) - Calculates the

auth_response:BASE16( SHA1_HMAC( auth_nonce, passhash ) ) - Sends another request, this time with a payload, to the server:

← POST /session/sign-in {"sid":<session_id>, "username":"john", "auth_response":<auth_response>}

[Step 4] The server:

- Calculates an

auth_token:timestamp ":" BASE62( SHA1_HMAC( passhash, server_secret ":" timestamp ) ) - Saves the

auth_tokenin the user’s session object - Verifies the

auth_responsesent by the client:BASE16( SHA1_HMAC( nonce, passhash ) ) == auth_response - Deletes the

noncefrom the user’s session - Responds with the

auth_tokenand a complete description of the user (name, email… things like that):

→ 200 OK {"auth_token":"xyz", "sid":"xyz", "user":{<user details>}}

The client stores the auth_token locally, to be used for future automatic re-authentication.

Later in time, when the client sends whatever request to the server and includes its session_id, the server will evaluate the following logic:

if session = Session.get(session_id):

if session.auth_token:

allow_request()

else:

perform [Step 4]

else:

session = Session.new()

→ 401 {"sid":session.id}

perform [Step 3], starting at point 4, and finally re-send original request (client)

Since [Step 3], point 4 and forward does not require user input, re-authentication—and thus backend fade-over—can be done completely in the background. The user experience will the that the original request (e.g. a click on a button to show some content) takes a little longer time than it usually would.

User interface

Since the user interface is created, rendered and maintained solely by the client (i.e. web browser), there needs to be some structure. The HTML DOM is actually a great view representation and in combination with CSS gives you control of each pixel on the screen, and at the same provides a nice separation between view structure and layout. However, these kinds of websites tend to have many different “screens”, or view states if you will, quickly making your regular HTML and CSS code a freaking mess.

Since the user interface is created, rendered and maintained solely by the client (i.e. web browser), there needs to be some structure. The HTML DOM is actually a great view representation and in combination with CSS gives you control of each pixel on the screen, and at the same provides a nice separation between view structure and layout. However, these kinds of websites tend to have many different “screens”, or view states if you will, quickly making your regular HTML and CSS code a freaking mess.

What we did was to have a mind set as if we where writing a desktop application — we define logical components in folders and files that reflect the structure of these components. We then process, or compile, these sources into machine-and-network optimized code (HTML, CSS & JavaScript), just like you do with “regular” software development.

A nice side-effect of having an intermediate “compile” step is that you can write your source code in whatever language suits you and your project — your no longer limited to the languages and coding styles dictated by web browsers. For instance, you can define your layout code in LESS instead of CSS and write your logic in Move instead of JavaScript.

Downsides to a “compiling” approach

This approach obviously has some downsides, one of them relatively painful: debugging. Since the code you’re running does not directly reflect the source files you have in your structure of logical modules, finding and fixing a problem becomes harder as you need to back-track and search your source for certain things. In the end, we took a pragmatic approach to this and simply generated human-readable code that’s annotated with the path names of the source.

Templates in the DOM

For views that aren’t permanent (most views aren’t) we are using HTML templates, kept inside the DOM as data-only node trees:

<module id="drops-drop">

<drop>

<h1></h1>

<img>

...

</drop>

</module>

With CSS making any module node tree a data node tree, exempt from layout and display:

module { display:none; }

Some module logic (e.g. JavaScript code) then clone appropriate parts of its template, which is made available to a module using the __html convenience variable:

// Register a hook for a certain URL

oui.anchor.on(/^drops\/(<id>[a-zA-Z0-9]{25,30})/,

function(params, path, prevPath) {

// Load data for drop with <id>

oui.app.session.get('drops/drop/'+params.id, params,

function(err, drop) {

// Make a new instance of the <drop> child node tree

// of our HTML template:

var view = __html('drop');

// Configure the view

view.find('h1').text(drop.title || drop.origin);

...

// Finally add the view to an active part of the DOM

mainView.setView(view);

});

});

Data storage and the problem of many-to-many

Since we have a very clean separation of data and presentation, CouchDB made a lot of sense to us. In CouchDB, data is represented by logical structured blobs called “documents” — basically it’s a key-to-JSON store.

Since we have a very clean separation of data and presentation, CouchDB made a lot of sense to us. In CouchDB, data is represented by logical structured blobs called “documents” — basically it’s a key-to-JSON store.

Dropular.net has a feature where you can follow any number of other users and look at a feed of images created by all those users. In data terms, this is a many-to-many relationship which when using a RDBMS like MySQL is expensive (computational wise). With CouchDB on the other hand, many-to-many relationships are very easy to define and they are cheap to maintain!

Basically, we lazily define a CouchDB view per user _design/user-drops-USERNAME/_view/from-following with the following map function:

function (doc) {

var following = %FOLLOWING;

var user, createdBy, created; // find lowest timestamp

for (user in doc.users) {

var t = doc.users[user][0];

if (!created || t < created) {

created = t;

createdBy = user;

}

}

for (user in doc.users) {

for (i=following.length; --i > -1;) {

if (following[i] === user)

emit([created, user], doc._id);

}

}

}

Example: GET http://dropular.net/api/users/rsms/following/drops →

{ "drops": [

{ "id": "9uQyA5tTraIkiVHG5l1XdPRHwfg",

"key": [1274772176060,"suprb"] },

{ "id": "cytCrjVJPQOCXiSqF1MV6GqPEt1",

"key": [1273706969465,"suprb"] },

...

],

"total": 2701, "offset": 0

}

Now, CouchDB will make sure to run this function every time any related document is modified, added or removed, effectively keeping all relevant “from-following” indexes up-to-date. CouchDB is very good at these incremental updates, so even though this looks complex and slow, this function is compiled to an internal representation and only run on the modified values, not the complete data set, making an update both atomic and complete within a few milliseconds.

As part of Dropular, I wrote a Node.js module for dealing with CouchDB that has a very low level of abstraction: https://github.com/rsms/node-couchdb-min.

Access points aka The Server

As any app that centralizes data, authentication, etc, you need something to serve as the hub. We call these access points, as they are the contact surface between the client application and whatever lives in the central backend (CouchDB, AWS services, etc). Since I’ve been involved in Node.js for a long time, Node.js was a given choice. Actually, this was such a successful solution that we sustained over 1000 API requests/second on one single small AWS EC2 instance with less than 1.0 in load (during our initial release which caused a thundering heard-like wave of visitors). Even for a commercial website, that number is considered good.

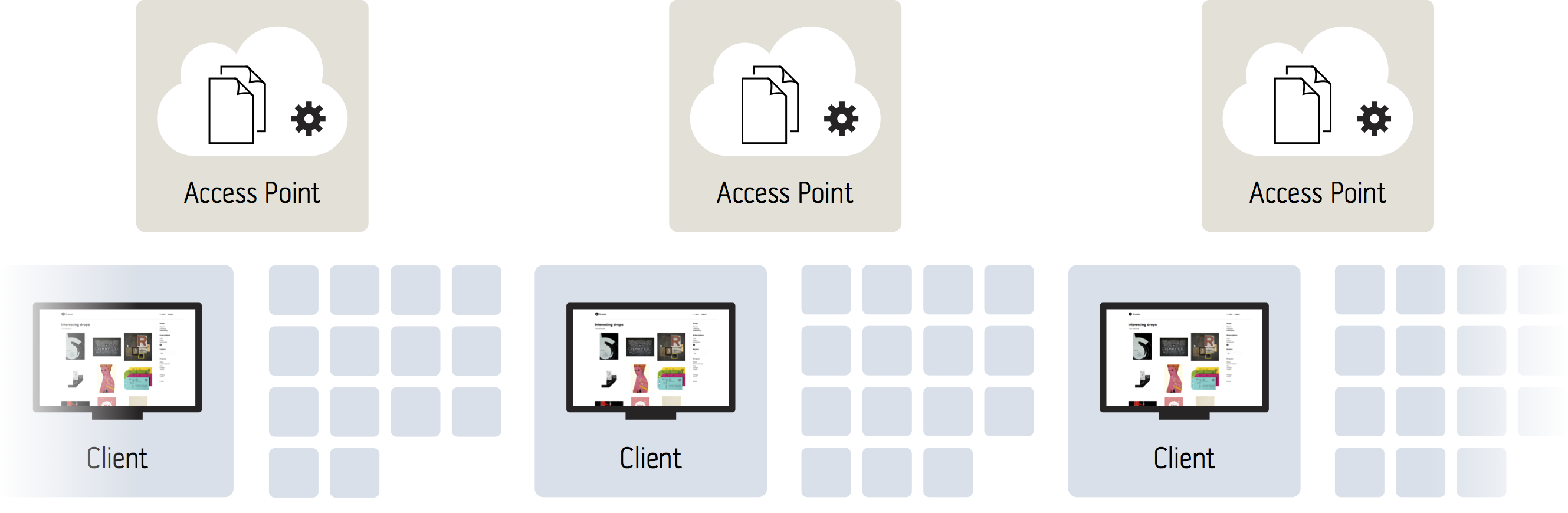

Scalability as an effect

The Oui app kit supports virtually an infinite number of access points to be used, making this approach of running all the logic in the client an extremely scalable solution.

— Just add as many access points as you need, effectively scaling close-to linearly (at least as close to linear as your backend dependencies allow).

A model which relies on persistent sessions or rendering of the user interface in a central location (i.e. on the server) can never reach this level of scalability-to-price/complexity ratio.

What’s next

Today, 21 months later, the current browser technology allows for even more sophisticated client-and-access-point solutions, where everything from complex image processing (canvas 2D and 3D) to data processing (WebWorkers) can be done client-side. DOM manipulation is much cheaper, JavaScript runs much faster and OAuth 2.0 is an easy-to-use (in contrary to 1.0), suitable authentication schema for these kinds of approaches. 3D-transforms for hardware accelerated, high-performance 2D and 3D user interface effects as well as host-native, fluent animations defined in simple CSS.

I’m really curious to see what’s next — the web is rapidly transforming from a “hacky” document presentation technology to a rich application development and distribution platform with standards that make sense. No more live hacking on FTP servers or behemoth HTML-generating Java servers.